This guest post is by Anne Galer. Thank you for your work, Anne!

With the help of the Abiquiu community, Cornerstones’ adobe experts and volunteers, preservation work on the Moque Morada is nearing completion. When the project began in early 2019, my structural assessment revealed large parts of the interior adobe walls had been melted by water. Faulty drainage from the old metal roof was allowing water to collect at the base of the exterior north wall, and windowpanes were broken. It was clear that intervention was needed before serious damage endangered the entire structure.

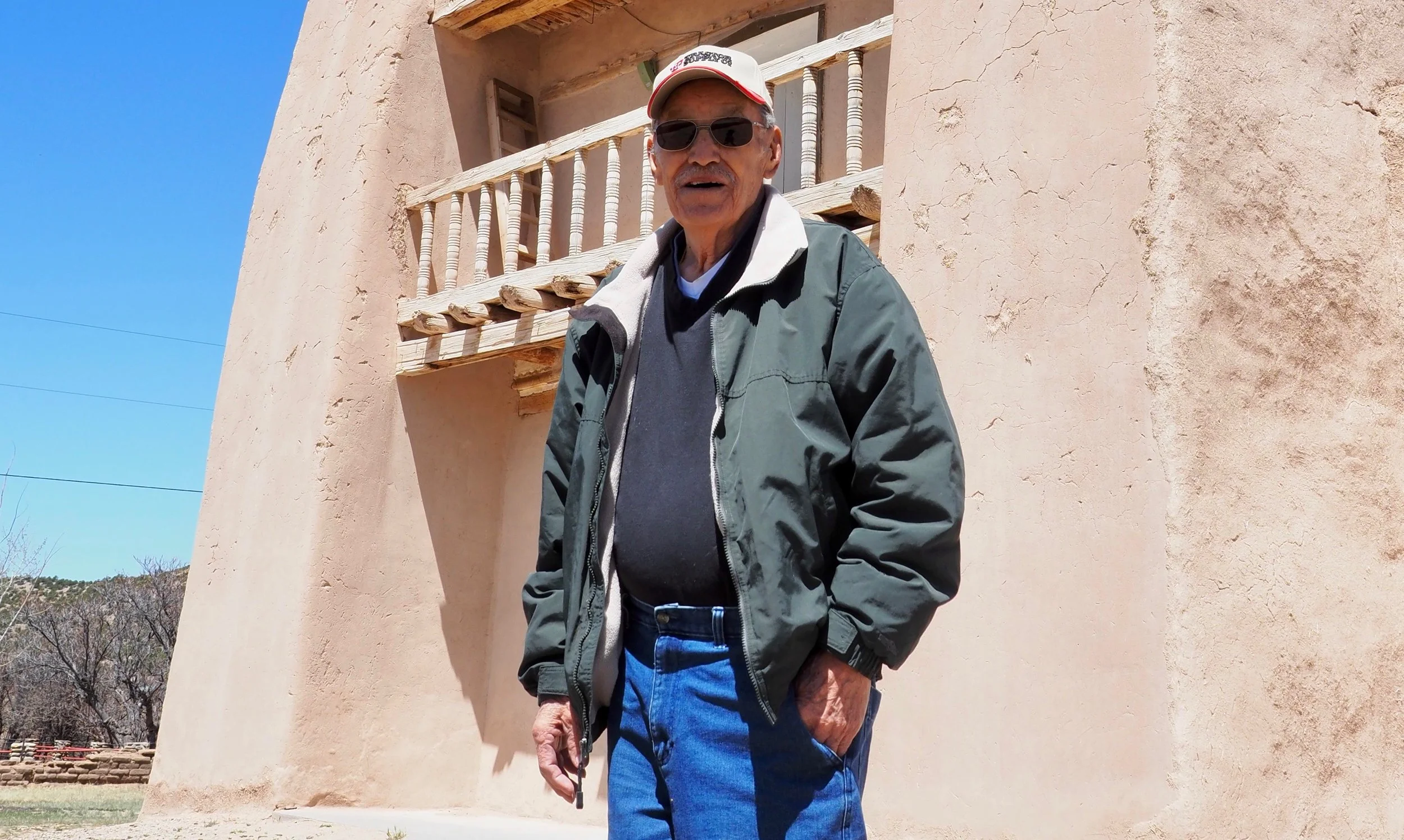

The Moque Morada is unusual in that women are its caretakers. Theresa Jaramillo, the Hermana Mayor of the morada, reached out, and Cornerstones got involved. Thanks to Cornerstones’ Stephen Calles, the metal roof which was damaged by winds and age was secured, and a new gutter and downspouts now channel water away from the building.

The biggest, and most time-consuming part of the project–repairing significant water damage to the interior walls of the east section of the building–was taken on by master enjarradora Angela Francis, who continues the historic New Mexico tradition of women adobe plasterers.

Before new plastering could begin, Virgil Trujillo and other members of the community hauled dirt from a traditional source and later helped sift and mix the soil into plaster. In a key part of her approach to the work, Angela did a series of test patches of different soils and mixes to find the strongest mud to apply.

Once preparations were complete, Angela started by removing loose dirt from a badly done patching. With her hands and a trowel, she built up the deeply coved sections at the top and bottom of the walls layer-by-layer and created an even base for subsequent finishing layers of mud plaster.

When I visited Abiquiu for the Santa Rosa de Lima festival in late August, Angela was putting the final touches of top coats on the beautifully smooth walls and carefully finishing off the kiva-style fireplace. A final coat, called aliz, is to be done with the pale yellow-brown local dirt used in the morada’s original construction.

Thanks to Steven, Angela, Theresa, and a community of volunteers the morada is in a good place to survive for another hundred-plus years. Great job!

Photos of Angela by Anne Galer.